|

| “You’re waiting for a train, a train that will take you far away. You know where you hope this train will take you, but you don’t know for sure. But it doesn’t matter…” |

How do you watch a movie?

With your eyes, idiot.

Let me start over.

One of the best theater-going experiences of my life was the midnight premiere of Inception. I had just finished high school and was spending the summer discovering Bergman, Godard, and Tarkovsky in the “Film Art” DVD section of my local library. I was engulfed in film. Immersed. And if Christopher Nolan is a master of anything, it’s that captivation. Audience manipulation. Because a Nolan film is a spectacle. Characters don’t speak, they pontificate. The scores are thunderous, the soundscapes are bombastic, and the editing crescendos into a montage that’s designed to hit you

Right

Before

The screen

Goes

Black.

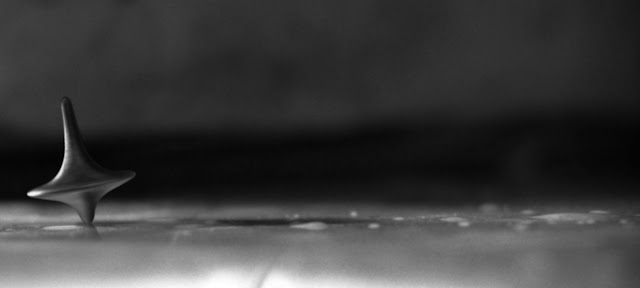

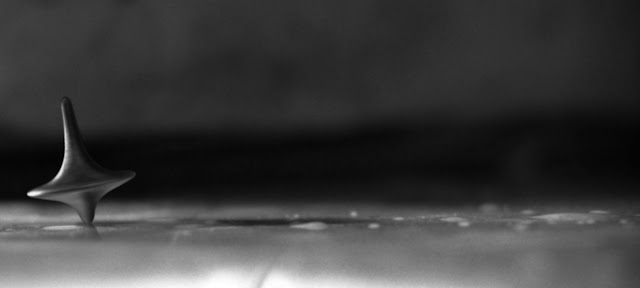

And so it was with Inception. Maybe your screening was similar. You’re on the edge of your seat as Cobb is coming off the plane and the music is swelling and he spins the top and he sees his kids and the top keeps spinning and it wavers for a sec—INCEPTION.

I will never forget that moment in the theater. The audience was a collective body that exhaled the moment the screen went black. It was communal and invigorating. I remember grinning widely as the lights came up, unable to do much else.

“What does it mean?” we all wondered. “Did the top fall or not?”

Nolan has since explained that the point of the scene is that, for Cobb, it doesn’t matter if the top falls or not because he’s back with his kids – that’s all that matters.

Cool bro but what actually happened after the title card came up?

The answer is: nothing. But a special kind of nothing.

We all know the thought-experiment of Schrodinger’s cat: inside a sealed box there is a cat and a flask of poison that will be released at some point in time. According to the Copenhagen Interpretation (which posits that physical systems do not have defined properties until measurements are applied to them), the cat is simultaneously dead and alive so long as you don’t open the box. This is known as Quantum Superposition. Quantum Superposition collapses into a singular reality the moment you open the box and apply properties to the cat, definingit as dead or alive.

Now, let’s apply this thought-experiment to Inception.

If the audio/visual narrative, the content of the film, is the cat and the movie itself is the box, the box closes as soon as the title card comes up – never to be opened again. We’re left with Quantum Superposition. We’re left with a paradox. And that’s what’s so great about Inception: it challenged the weekend moviegoer to embrace the thrill of ambiguity. To sit in uncertainty. To let the last question linger. Forever.

What happens if you leave it there?

What happens if you don’t try to re-open the box?

In her landmark 1966 essay “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag argued that the art world had become overrun with hermeneutics; that criticism was too hung up on the content of a work and the meanings it might contain. “From now to the end of consciousness,” she lamented, “we are stuck with the task of defending art.” Rather than enriching a work of art, Sontag believed that “to interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world – in order to set up a shadow world of ‘meanings.’”

Rather charmingly, though, in 1966, this overabundance of interpretation had not yet reached film criticism “due simply to the newness of cinema as an art.” Oh, Susan. How I’d love to hear your thoughts on Film Twitter and the countless video essayists that plague my YouTube homepage.

What Sontag argued for, in approaching all works of art, was what she called transparence: “the luminousness of the thing in itself, of things being what they are.” Interpretation of art, in this case, misses the point of art altogether. Rather than focusing on the content of a work and trying to add to it – inserting analysis, theory, metaphor – “our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.” “The function of criticism,” she said, “should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.”

We all want answers. More importantly, we all want to be the one with the right answers. And it’s exhausting. For critics and writers, it’s helpful to have a

take, an angle, when discussing a work. It makes the piece easier to write, and it makes the piece more approachable to read. Nearly everything I’ve written on this blog has used that method of criticism. But as Susan Sontag warned, sometimes when we try to enliven a work with our own ideas, we end up forgetting about the thing itself.

Art, I believe, works best when it is both communal and intimate. When it can speak to everyone while seeming as if it holds secrets just for you. This superpositioning diminishes the more you try to uncover it. Now, I’m not writing this piece to try and convince you to stop analyzing, discussing, or interpreting movies. If this blog is to continue, those methods will be implemented in one form or another. But we have to remember that movies, first and foremost, are not made to be dissected, they’re made to be experienced firsthand. So if you want to get the most out of a movie, you have to pay attention to what eyes you’re watching it with.

Okja is a great movie on Netflix. It’s fun and heartfelt and exciting and it has a straightforward narrative and message. The Fits is a great movie on Amazon Prime. It’s intriguing and rhythmic and naturalistic and, while it might not provide concrete answers to every question it raises, it remains compelling and watchable. It’s not trying to trick you. It’s not trying to be smarter than you. We just aren’t accustomed to movies that don’t spoon-feed us their messages. Upstream Color is one of my favorite movies of this century (unfortunately, it just went off Netflix). It’s dense and atmospheric and puzzling. I’m sure there are countless diagrams, analyses, and interpretations online that breakdown the rather obtuse plot.

What they can’t answer, though, is how you’ll feel watching it. They could not possibly predict the free-associations your brain will make while watching the film, how you’ll react to being puzzled, or what your initial response to the film will be upon its completion. I believe those are all special moments important to the cinematic experience of any movie.

Discussion and analysis can enrich a movie, but neither should work to diminish or supersede the experience itself. To paraphrase the Franciscan friar Richard Rohr, do not be so eager to answer that you forget to wonder. Experience a movie viscerally before you approach it intellectually. Dwell in ambiguity. Embrace quantum superposition. Cut back content so you can see the thing for what it is.

So, how do you watch a movie?